Webinar

The War Below: The Global Battle to Power Our Lives

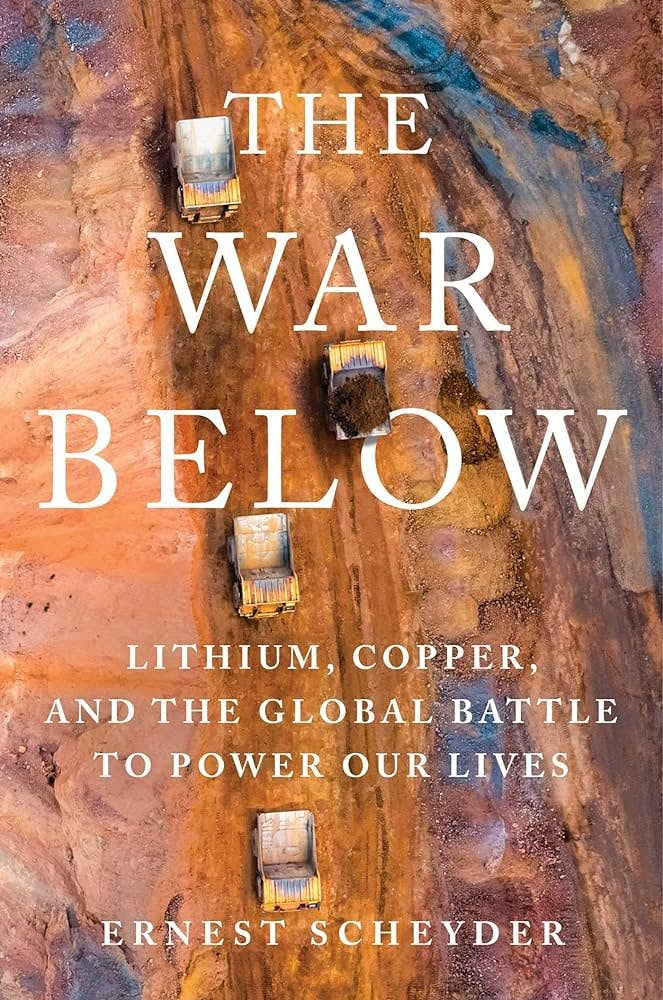

In this compelling discussion, host Drew Wandzilak from Alumni Ventures welcomes esteemed author Ernest Scheyder, whose book, The War Below, is longlisted for the National Book Award for Nonfiction and the 2024 Financial Times and Schroders Business Book of the Year Award.

See video policy below.

Scheyder provides an unprecedented look into the global battle over essential materials like lithium and copper, which are critical for powering our lives through electric vehicles, solar panels, and other technologies. He delves into the complex tensions surrounding mining, revealing the struggles between industry leaders, conservationists, and local communities, all while painting a nuanced picture of energy independence. With illuminating writing, Scheyder shares the human toll of this conflict and explores why recycling and newer technologies face challenges in achieving widespread adoption.

Don’t miss this opportunity to understand the stakes involved in the race for energy resources!

“The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives” by Ernest Scheyder delves into the complex global struggle to secure essential minerals like lithium and copper, which are vital for technologies such as electric vehicles and renewable energy systems. Scheyder examines the intricate conflicts among industry leaders, environmentalists, indigenous communities, and policymakers over mining operations that often threaten sensitive ecosystems and cultural sites.

Reasons to Join:

- HomeGain insights into the complexities of the energy transition from a seasoned journalist.

- HomeUnderstand the implications of mining on climate change and local ecosystems.

- HomeExplore the challenges and potential solutions in securing materials essential for a sustainable future.

Alumni Ventures is America’s largest venture capital firm for individual investors.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ

Speaker 1:

Hello everyone. I’m Drew Wandzilak. I’m a senior associate here at Alumni Ventures where I help support our US Strategic Technology Fund. I am so glad that you are all here with me today as I interview Ernest Scheyder, who is the author of The War Below: The Global Battle to Power Our Lives.

A little bit on Ernest and then we’ll jump into the interview. He’s an award-winning journalist, a senior correspondent for Reuters. He specializes in energy, critical minerals, and the global energy transition. In 2024, he published The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power Our Lives. It’s a critically acclaimed book on the human and geopolitical dimensions of the energy transition—specifically around mining.

He’s a veteran reporter. He has covered the U.S. shale oil boom, the clean energy shift, and the critical mineral supply chain all the way from North Dakota to Vienna. He also reported on the 2020 U.S. presidential election and co-won a Society of News Design award for an investigative series on deep-sea mining. His work has appeared in Time, Barron’s, and Marketplace. Based in Houston, he is a frequent panelist and advocate also for Alzheimer’s research.

The War Below, as I mentioned, dives into this global battle for critical minerals and materials like lithium and copper—essential for the clean energy transition. It reveals the clashes between industry, conservationists, and communities, highlighting the environmental, human, and geopolitical stakes of the energy transition.

I hope you enjoy my conversation with Ernest. Let’s jump into it.

Hello, Ernest. Let’s jump into it. Thanks for coming on with us today.

Speaker 2:

Hey, it’s great to be with you, Drew.

Speaker 1:

Alright, so let’s dive right in. Your book The War Below obviously focuses on these critical minerals, materials, and mining—which has long been a pretty divisive topic. It’s essential for powering modern technology. Really, the world around us is surrounded by goods and things that were originally sourced from mines, but it’s also been kind of vilified for its environmental and social impacts.

What inspired you to write this book, The War Below, and what do you hope that readers take away about the complexities and considerations of mining in today’s world?

Speaker 2:

Sure thing. So in my day job, Drew, I’m a journalist and I write about the critical minerals space. And the book really draws its inspiration from my time chronicling the daily machinations of the critical minerals industry.

But I will go a little farther back in time. Before I covered the critical minerals space, I wrote about oil and gas for the better part of a decade. I actually lived for about two years in North Dakota writing about how technological innovations—via fracking, horizontal drilling, and other measures—really helped make North Dakota one of the world’s largest oil-producing regions.

I love to share the anecdote that I moved to North Dakota from New York City and my rent in North Dakota was more than double what I was paying in New York City. So I think that goes to show you the supply and demand imbalance at the time of that big boom.

But I found when I covered the oil and gas industry that people tend to fall into one of two camps. Either, in general, folks say that oil and gas is great for our global economy, for our way of life, and helps lift standards of living everywhere—or folks might say, doesn’t oil and gas have some sort of harmful effect on our planet and contribute to climate change?

And I recognize that that might be an oversimplification, but in general, I found that when I covered the industry for, as I say, the better part of a decade, folks tended to fall into one of those camps.

But when I switched my professional day job coverage area to focus on critical minerals, I did so partly because I was curious about the energy transition and where we as humans hope to get the building blocks to power that.

And I found, in general, the average person on the street said, “Sure, that sounds interesting. Have fun. I think there’s lithium in my cell phone. I think there might be some lithium in my remote control for my television.” But people would say that sounds interesting.

But when it came to specific projects—when it’s like, “Hey Drew, we’re going to put a mine where you went camping as a child,” or “We might need to dig where there’s an Indigenous holy site,” or there’s a potential harm to an environment or an ecology—that’s where the opposition added up.

And so the more I covered each of these proposed projects in my day job as a journalist, I became very curious around where and how not only the United States but our planet hopes to get the building blocks to respond to climate change, to meet the targets of the Paris Climate Accord, and even to power the devices that are increasingly ubiquitous in our everyday lives—that is, electronic devices.

I mean, the cameras with which we are speaking to each other right now would not have been common five or ten years ago, and now everybody’s got a camera and is doing Zoom calls. And those are obviously all connected with copper wiring and built with critical minerals.

And so these are the questions that I’m exploring with the book that I really wanted to bring to the audience. At its core, the book asks: What are the choices we’re willing to make if we want this energy transition and this electrified future? And who are the communities affected? And do we think through those topics of community and choice as often as we should be doing?

I wanted to humanize these topics for the reader and to introduce the reader to people across the spectrum who have various views on extractive projects across the country—and really the world.

So that was my goal with The War Below: to bring these complex questions to folks of all stripes and to say, “What would you do if you were in a regulatory or policymaking decision authority? And how would you hope that these issues get addressed as we move forward into the 21st century?” Because we know that whoever controls the production and processing of these critical minerals will control the 21st-century economy the way that control of oil and natural gas defined the 20th-century economy.

Speaker 1:

I of course want to jump into the strategic importance, but before we do, I appreciate you bringing up the oil and gas anecdote because in many ways I think these stories are intertwined. I mean, energy—not just the connection of the materials needed for energy production—but also I think the public sentiment, the policy sentiment around it is very similar. Kind of those competing elements of: we want energy abundance and we want material abundance, but we also have to consider the environmental or social impacts.

And sometimes these things are operating against each other, and sometimes, to your point, to meet some of these energy transition standards, they’re actually working in concert with each other.

You made a great point about the strategic importance. I don’t want to say it’s not a surprise, but it’s maybe not news that the U.S. has kind of lagged behind building secure domestic supply chains. We seem to be getting lucky more often than not in finding reserves of materials within our borders, but still we’ve kind of lagged, I think, when it comes to lithium and copper in the long term—compared to somewhere like China.

In light of global supply chain disruptions—we saw this with COVID—and then even just our emphasis on dominance and strategic importance in the world: how critical is it for the U.S. to develop these domestic sources of lithium, of copper, of other strategic minerals, and how are you seeing that landscape develop?

Speaker 2:

Yeah, great question. You mentioned the pandemic, and when I think through these issues, I actually think back to the pandemic, Drew. It was about four or four and a half years ago that we in the United States discovered that as this pandemic was inching its way across our planet and masks became required, many in the U.S. were shocked that the U.S. didn’t make any masks.

They said, “Here is an item that’s now ubiquitous, that’s necessitated everywhere—you can’t go to the grocery store without a mask—but none were made in the United States.” And so for a while, there was actually a shortage of masks and folks weren’t able to access them.

And I think that crystallized for a lot of Americans the sometimes sleepy topic of supply chains. It’s not the sexiest thing to think through—supply chains—but obviously it’s critically important.

And so now you just sort of take that thought pattern and you put it onto our energy transition. You put it onto our increasingly electrified economy.

And so you think through: okay, where we get the lithium and the copper and the nickel and the other critical minerals actually matters. And I would say, Drew, that if the promise of this energy transition is reduced carbon emissions, the extremely long supply chains right now are not actually good for reducing carbon emissions.

I mean, take lithium for example. One of the largest lithium-producing regions in the world is in northern Chile—Atacama Desert. Two of the world’s largest lithium companies operate there: SQM and Albemarle. Lithium is extracted from brine operations there, shipped to the Chilean coast, where, depending on the operation, it could be lightly processed. Then it’s shipped across the Pacific Ocean to China—usually—where it’s processed further into a type that can be used to make a battery’s cathode.

And then it might be shipped to another part of Asia to be put into a battery’s cathode. And maybe it’s put into a battery pack there and then shipped back across the Pacific Ocean to, say, an auto plant in maybe Nevada, where it’s put into an EV that ends up in your driveway.

And that’s twice across the Pacific Ocean.

That means that that lithium supply chain, in this hypothetical example, can be disrupted by weather, by other natural events, by armed conflict, by any number of other disruptions right there.

So what would it mean to have a more localized or even North American supply of lithium? You would certainly have far fewer carbon emissions just from transportation. You would have less of a potential for disruption. And you would have—maybe not energy independence—but sort of more energy security might be the term.

And yes, the 1990s and 2000s were all about globalization, but there’s a huge trend—certainly as you and many in the investment community know—toward more regionalization right now.

And so having that more regional focus and regional security of supply is only going to help this electronic transition that’s happening right now.

Speaker 1:

And the scenario that you just outlined—the existing state of the supply chain for many of these minerals—it obviously goes through this long path. So I want to bring in this question from our community, which is really thinking about: how do we analyze and track something that goes through that supply chain?

And maybe, to your point, as we regionalize this and we bring these facilities and supply chains onshore, it reduces the need for this. But in the time being, when we’re thinking about environmental degradation, we’re thinking about child labor—whatever it is—I think people are becoming more and more aware about analyzing where the goods and things that they have come from.

And that’s obviously a big focus of your research. People have suggested blockchain as a potential avenue to do this—obviously with privacy and the permanent nature of it.

How do you think about traceability of these minerals? Do you think blockchain could be an option? Or is it more, “I actually don’t think—we’re going to onshore a lot of this and the tracing of the supply chain lines isn’t going to be as important going forward”?

Speaker 2:

Yeah, so I might give you a non-answer to your question—or maybe approach it in a slightly different way. I’m going to say both.

I’m going to say I think there’s huge potential for blockchain, but yet there’s still going to be the problem that exists that requires us to assess, to think through, and to have this collective wrestling.

So blockchain, I think, is an extremely interesting technology that can track the provenance. But you, of course, need to have the entire supply chain—from mine all the way to manufacturer—be completely committed to that, including paying for it, including having an end customer that is demanding it. And that’s not necessarily always the case.

And as an example, I might say: you might have a copper industry that’s, for instance, much more attuned to this and much more willing to participate in a blockchain provenance-type scheme from mine to manufacturer.

Speaker 2:

But there are other critical minerals industries that have not been as big as the copper industry and are increasingly in demand. Cobalt is a great one right now. And so we do have a situation where, sadly, in some cases you can have child labor be part of the cobalt supply chain, and it can be near impossible to prove.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, there is a huge artisanal mining community. And that term essentially means that you have amateur miners, some as young as six or seven, that dig near or on certain mine sites and basically take rock out of the ground. And the percentage of the cobalt in that rock is extremely high. So the rock could be sold to a middleman, who then takes it to a processor, who then sells it into the global cobalt supply chain. And it can be impossible, in that scenario, to determine if the cobalt in your smartphone, for instance, was taken out of the ground in that process I just described.

Now we know, certainly, mining can be a very dangerous career. That’s why we have high safety standards in the United States and other Western nations for this. And so having children as young as six or seven that are part of that production supply chain obviously can endanger them. Sometimes you have some children losing limbs or even dying. There are horrible stories out there. And so it’s very impossible, though, to track that currently.

And so what would it look like to really have more of the manufacturing supply chain demand more transparency? And what would it also look like to say that we need to be having more cobalt facilities—not in the DRC or elsewhere—be producing this critical mineral?

Earlier this year in my day job, I wrote a story about the only cobalt mine in the United States. Now, this company that owns it spent millions of dollars building it and got right up into the actual opening—and then never actually opened it.

And part of the reason they never actually opened it is because production in the DRC was increasing rapidly in a pretty transparent bid for market share. So these mines were operating below their operating costs, essentially losing money. And they were doing that to push out other foreign rivals. And in this case, this cobalt mine in Idaho never actually opened.

Now, this mine in Idaho has a much higher operating cost because it uses union labor, it uses talent that is paid a living wage, it uses high safety standards and has high emergency training, etc., etc. All of those things have a cost.

And so I mentioned I would give sort of two answers to your question. I mean, I think yes, it is blockchain, but also it involves a question around: What are we as consumers willing to pay? Are we willing to pay more for a product that’s made with cobalt or other critical minerals that are produced in regions of the world where we know that they’re produced at higher standards—or, at least in our regions? Or I should say, actually, and in our regions, to ensure greater stability of supply?

These are some of the tough questions that I really wanted to bring to the reader with The War Below.

Speaker 1:

And of course, I mean, you bring up the DRC, its strategic importance—and it’s been an area that I think China has had pretty much a stranglehold on. And correct me if I’m wrong—the U.S. has been relatively absent from that market.

Any clarity or story on kind of why that is? I think there’s an effort to bring these things here, but I mean, you even said it—it’s difficult to get over the finish line domestically. But these things are strategically important. Costs are extremely important.

So why aren’t we a bigger force—we, as in the U.S.—a bigger force internationally in kind of these regions that are now victims of corruption or whatever it may be? And we’re missing out?

Speaker 2:

Sure. For the book The War Below, I had the great honor and privilege of really speaking with a whole host of folks, including executives from Freeport-McMoRan, which is the world’s largest copper producer right now. They used to own several large mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, but were forced to sell them due to economic dire straits that they found themselves in after an ill-timed investment in the oil and gas industry. Oil and gas prices plummeted, and that took the company’s balance sheet with it.

And so here you had an American-based company that was really trying to institute best practices in its operations across the world, including in the DRC, and it had to sell these in order to essentially stay alive.

And who was the buyer? It was a Chinese company. And this was the highest bidder here for this project. And so the company—Freeport—sold these assets reluctantly, as I chronicle in the book.

And what we have today is this unfortunate situation where you do have safety and other ESG concerns in these operations there. And there was some consternation—I think is the right term—as to why Washington didn’t step in and try to find maybe a different buyer or to stop the sale.

And could it have stopped the sale if it wanted to—from an independent company operating in another country? I think these are all sort of the, as we say in American football, Monday morning quarterback–type questions that folks are bringing up right now.

But what is realistic is that there are these huge safety questions around those operations. And what would it have looked like if those sales didn’t go through, or if there was perhaps another economic incentive or other structure for the company before it sold?

We do have several attempts by Washington to maybe abrogate China’s influence in the world right now. I think the biggest example is the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act, which offers tax credits for EVs that are made with critical minerals produced in certain countries that have U.S. free trade deals.

The DRC is not one of them. But Chile, Australia, and others are countries that do have U.S. free trade deals. And so that sort of creates, maybe, a two-tier structure of countries across the world. And countries like the DRC or Zambia that do not have U.S. free trade deals are getting outreach from the U.S. State Department right now for encouragement of foreign investment, encouragement of better mining practices in those countries.

I think it’s obvious to many of us that we’re going to have a change in U.S. administration here come January. So how that effort goes forward—we will see. But right now, there is a huge push for Washington to do more to boost mining standards across the country—and across the world, really. And how those play out moving forward, I think, will be very, very interesting.

I mean, I think what we’ve seen with the Biden administration and the incoming Trump administration is a definite interest in critical minerals, but perhaps with different approaches.

I mean, I think the Biden administration has taken an approach that climate change is extremely existential and needs to have our full focus. And I think that sort of shades how they have approached certain mineral transactions, deals, and other incentives that are out there.

And I think the Trump administration, certainly in the first term, approached these issues from a national security perspective and said, how do we ensure that America strives for—not necessarily energy independence—but perhaps energy security in a better way?

And regardless of your views on electric vehicles or not, I mean, we are going increasingly electric. So where we get these building blocks matters.

Speaker 1:

I think it’s a great point. A brief tangent—I mean, we spent some time in nuclear energy, and that’s often been the commentary when we’re asked about the election and the results, of what the new administration is going to look like.

And you had one administration—you had a lot of Democrats that talked about things like nuclear as a form of curbing climate change. It’s an environmental push.

And then you had, I think, the other side of the aisle going, “This is what we need for energy abundance. This is what we need for energy independence or security.” So I think we’re hearing that a lot.

Speaker 2:

Drew, I would just add to that—I mean, I get asked a lot, especially when I talk about The War Below, “Well, what about nuclear? Could that not solve this? We don’t need to dig a hole in the ground.”

And then I point out—well, yeah, we do. I mean, uranium, it comes from a mine. And so we get back to sort of the existential question at the heart of the book: What are the choices we’re willing to make?

And yes, nuclear has a whole host of questions—sort of beyond “Do you dig a hole in the ground or not?”—but it starts at least with that hole in the ground. It starts with the uranium mining.

You can’t have a nuclear power plant without uranium. So for me, it gets back to these core questions around choice and community that I really hope folks think through more.

Speaker 1:

Absolutely. I mean, I think with anything this large, right, there are—and the reason you could write a whole book on it—is because there are so many elements to this and balances and trade-offs.

You touched on it briefly—we just chatted about the incoming administration. I’m going to ask you to just make a prediction, and I won’t hold you to it, but I mean, what do you think the trajectory is going to look like?

And I’m not asking you to necessarily comment directly on policy, but I mean, are you hearing anything—based on history, whatever it may be—on just the general direction of U.S. policy when it comes to mining, when it comes to minerals?

Is it going to be, I think, more of a foreign approach and we’re going to get more ownership and more control in these areas that are of strategic importance? Is it going to be a focus on onshoring and what can we do here at home?

Just predictions—kind of thoughts around that.

Speaker 2:

Well, I think let’s just look at the first Trump term and some of the projects that President Trump—45—did approve.

He approved the Lithium Americas Thacker Pass mine just before leaving office. This is one of the largest U.S. sources of lithium. It’s under development right now.

He approved the Resolution Copper project—one of the nation’s largest sources of copper—that is tied up in litigation right now. And so we’ll see what happens with that.

But he did block the Pebble Mine, which is in Alaska, which would be a massive source of copper and nickel and other critical minerals.

But by and large, he has been supportive in his first term of critical minerals projects.

Then I think you look at steps that some of his nominees have taken around these issues, and I think that is interesting to think through.

Senator Marco Rubio—the Secretary of State nominee—has been very, very hawkish around China’s attempt to influence the global economy.

Speaker 2:

He has sponsored legislation related to rare earths and other critical minerals in his time in the U.S. Senate, and he has been very focused on boosting America’s economy, especially on the international stage.

When we look at Chris Wright, who is the nominee for the Secretary of Energy position—yes, he runs a fracking company right now, but he also sits on the board of a critical minerals royalty company. So critical minerals are issues, obviously, that are known to him.

And Doug Burgum, the nominee for the Secretary of the Interior position, yes, is the governor of an oil-producing state—North Dakota—but North Dakota also has a large mining industry within its borders as well.

So I think when you look at the first term and then you look at some of the folks that have been nominated for his cabinet right now, you get a sense of generally an approach to extraction that is perhaps more favorable than past U.S. presidential administrations.

But I’d be curious around how some of the infrastructure—especially around the IRA—that has been developed these past few years, how that gets carried forward, if at all, and what does that look like?

I mean, certainly we’ve all seen the think pieces that sort of point out that the IRA can’t just be gotten rid of without an act of Congress—and of course that’s true—but are there other parts that could be slow-pedaled? I think we’ll see. And these are things that AI and others, I know, will continue to look out for.

Speaker 1:

Well, Ernest, I think you picked a good time to write a book about mining. And I think the new administration is still filling gaps, so I don’t know what’s next for you—I don’t know if it’s somewhere in policy or politics—but you certainly have the expertise that I think will be really important as we think about the next decade or so.

This was fantastic. Thank you for all of your thoughts. We obviously want everyone listening to buy your book and read more and learn more.

What didn’t we talk about today that’s in there that you think is important, or people should be looking forward to when they go on Amazon?

Speaker 2:

So when I think about these broader issues, as I mentioned—for me, this is about community and choice.

Each chapter in the book talks, yes, about a specific project, but each chapter uses those projects as sort of indicative of a broader theme. So the narrative spine of the story is about the Rhyolite Ridge Lithium Project, which is about 200 miles north of Las Vegas in Nevada. And this is home to a rare flower found nowhere else on the planet—as well as a massive deposit of lithium.

And so right from the beginning of the book, you get the question: Okay, well what matters more—this flower or the lithium there? And for some people, that’s a very easy choice. But for many other people, it’s not so easy a choice.

And so the tension that I’m bringing there to the reader is: Does biodiversity matter more than the climate change mitigation crisis?

Another chapter in the book talks about the Resolution Copper project in Arizona, which would have developed—and destroyed—a site considered very sacred to Indigenous communities, where they worship their deities.

And so right from the beginning of that chapter, you get asked the question: What matters more—Indigenous religious rights or copper for the energy transition?

And so regardless of what actually happens with these projects, the questions, I think, are core for the reader to think through.

We might have debates in the future around whether it’s deep-sea mining, for instance—which is part of the latter part of my book—but there could be other questions that come up. Should we be mining asteroids? Should we be looking for other sources of critical minerals?

If lithium goes away in the future and we make sodium batteries—for me, those questions are still there. So regardless of the fate of any specific project or technological advancements in the future, we know that we’re going to increasingly be a materials-based economy.

We might not get rid of oil and gas completely, and there might be sort of a hybrid approach, I think, for our global economy. But as we are increasingly a materials-based economy, these issues are going to come up more and more.

So having this collective debate—not only in the United States, but I think globally—is extremely important. Not just for every country, not just for investors everywhere or RIAs everywhere, but for environmentalists, for conservationists.

And we have the U.S. Thanksgiving holiday coming up, and I’m not going to encourage dissension or fighting, but I would say—having these conversations, maybe at your Thanksgiving dining room table, might not be a bad idea.

Speaker 1:

I think it’s a great point. The book is educational. It’s an enjoyable, exciting read. But I think the best thing is all the conversations that you’re starting and the dialogues that you’re starting—because like we said, this is going to shape the next few decades, not just here in the U.S., but globally.

I think completely. Ernest, thank you so much for taking the time today and we really appreciate it.

About your presenters

Overview:

Drew Wandzilak invests in breakthrough technologies that matter to the real world—systems that generate power, move hardware, secure nations, or decode biology. He focuses on companies operating in high-heat, high-speed, high-stakes environments where technical performance is existential and strategic value is measured in megawatts, meters per second, or mission success. Across aerospace, energy, and defense, Drew backs founders who don’t just pitch vision—they bend atoms, trajectories, and supply chains to make it real.

Funds actively worked on:

Yard Ventures

Green D Ventures

U.S. Strategic Tech Fund

Investment Areas of Focus:

His investment lens prioritizes platforms over point solutions, scale advantages rooted in physics or manufacturing, and mission alignment with long-term public interest. That includes nuclear reactors that deploy like data centers, orbital vehicles that reshape access to space, hypersonic systems built for rapid iteration, and genetic tools that bring diagnostics to the edge. These aren’t just technical moonshots—they’re foundational bets on how the next century will be powered, protected, and personalized.

Drew led Alumni Ventures’ investment in Impulse Space, which is building the in-space logistics layer for a high-frequency orbital economy. He backed Aalo Atomics, a small modular reactor company designing standardized, factory-built nuclear power for grid-scale deployment. He also invested in Astro Mechanica, which is reinventing hypersonic aerospace testing for the modern battlefield, and Acorn Genetics, which is miniaturizing genomics to enable low-cost, distributed DNA testing anywhere.

These companies reflect Drew’s broader strategy: to invest in enduring platforms that serve strategic industries and unlock decades of downstream innovation. He believes the next great venture outcomes will come not just from apps or algorithms, but from reengineering the physical world—and the infrastructure that underpins it.

LEARN HOW TO INVEST IN COMPANIES IN THIS SECTOR WITH ALUMNI VENTURES:

U.S. Strategic Tech Fund >>>

Ernest Scheyder is a senior correspondent for Reuters and the author of “The War Below: Lithium, Copper, and the Global Battle to Power our Lives,” which has been longlisted for the 2024 National Book Award for Nonfiction and the Financial Times/Schroders Business Book of the Year. Fortune, The Wall Street Journal, BBC World, the Financial Times, Forbes, Science, the Christian Science Monitor and others have praised the book, which was named one of the Best Books of 2024 So Far by Amazon’s editors. Daniel Yergin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of “The Prize,” said the book “vividly captures the physical and political landscapes over which the future is being fought.” A native of Maine, Scheyder previously covered the U.S. shale oil revolution, politics, and the environment. His interest in journalism and writing began when he founded his high school newspaper. He is a graduate of the University of Maine and Columbia Journalism School. Visit him at www.ernestscheyder.com.